Who was Miss Dutcher?

Very little is known of Miss Dutcher's

life and career. This article adds a few details unknown until now,

but most information about her life seems to be lost forever.

Her full name was Sarah Louisa Dutcher, but she preferred Sally/Sallie.

She was a daughter of Moses A. Dutcher and Sarah Burchall

(or Burchill), and born in Tasmania,

probably on September 14, 1844. Her mother Sarah,

a weaver from Bethnall Green near London, arrived to Australia

in January 1841, one of 190 female convicts

expelled from England. She was said to be 18. Sallie's father,

Moses Dutcher, was banished to Australia in 1839 by a British court,

for his participation in an uprising of Canadians

against British rule of Lower Canada, known as the Patriots' War.

Many U.S. citizens participated in this rebellion, and

court documents at the time of his capture identify

Moses as being from Brownville, New York. He may have been a recent British immigrant to the area.

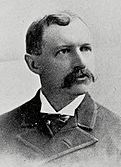

Sarah (Sally) Dutcher, from

Watkins' photo, now in the

Yosemite Museum.

In the 1880 Census, Sarah stated that both of her parents were born in England. According to

Samuel Snow's narrative, published in Cleveland in 1846, when other

rebels were pardoned and returned to their homes "only one, Moses Dutcher,

who married in VDL [Tasmania], seems to have voluntarily stayed in the colony".

A genealogical source shows Moses and Sarah married at All Saints Church

in Swansea, Glamorgan (Tasmania), in 1844. Little Sally was probably their

first-born. Another daughter, Jennie E. Dutcher (or Jane) was born

within the next few years. Just before Christmas of 1849, Moses, his wife,

and two daughters boarded the British bark "Eudora" on her way to California.

However, seventy days later, when the ship finally reached the port of Honolulu,

the Dutchers made a change in their plans: rather than to continue the

journey, they decided to stay at least temporarily

in Hawaii. A son, Moses A. Dutcher (Jr), was born to the Dutchers in the tropical paradise probably in March of 1851. In about May of 1851, Sally's father opened a boarding house

at the corner of Hotel and Fort streets in Honolulu. He died in Hawaii probably before 1855, when Sally was about ten or eleven years old.

In the late 1856, her mother married William Pearson, the owner of the White Horse Hotel in Honolulu. Mr. Pearson's life ended under strange circumstances in July 1860. His body was found in a well behind their house in Honolulu. Eventually, cause of death was ruled a suicide.

The Friend, published in Hawaii, announced that

"Misses Jane and Sarah Dutcher" had left Honolulu aboard bark Comet

for San Francisco on May 24, 1862. An article in San Francisco's

Daily Evening Bulletin of June 12, 1862, shows the arrival of

Comet on the previous day, with "Miss S. Dutcher and Miss J. E. Dutcher"

amongst 20 other names in the passenger list.

Sarah was about eighteen years old when she reached California. Her brother Moses Jr and her twice-widowed mother also

found their way to San Francisco

in mid or late 1860s. In California, her mother would marry for the third time, to one Mr. Clark about whom nothing is known. She died in June of 1870, still in her fourties. Interestingly enough, another Dutcher, a young man named Edwin M. Dutcher, will be one of Sally's companions in San Francisco, but he was most likely a relative on her father's side rather than her brother.

Between 1868 and 1871, Sarah is apparently focused on

fighting her way up into the social elite of

San Francisco, and some newspaper reporters are paying attention.

For example, Sarah attends the Carnival Ball at the Pavillion in 1868

("Miss Sallie Dutcher was a very charming peasant girl, in a blue skirt,

white waist, coquettish apron and hair neglige"). In 1871, the reporters spotted her twice: at the Merry Mascquerade of the Skating Club ("Miss Sarah Dutcher was

a peasant girl, and wore a costume which must have

temporarily ruined her yeoman father"), and at the Reunion of the Ivy Social

Club. Then, after 1871, her name disappears from social chronicles.

Sarah's sister Jennie got married in January 1871, but she died three years

later in San Francisco. In the coming years, Sarah's brother Moses and cousin(?) Edwin, who both were in some ways involved in a photographic business, moved out of town, and by the summer of 1874

Sarah is all alone. In San Francisco directories from mid 1870s she is listed as

"Miss Sallie L. Dutcher", or simply, "Miss S. L. Dutcher".

In April 1874 and March 1875 directories,

Sallie's occupation is "saleswoman with Carleton E. Watkins",

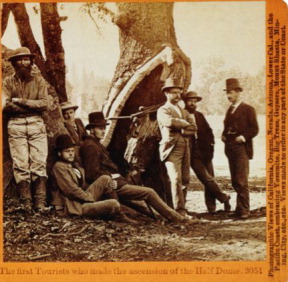

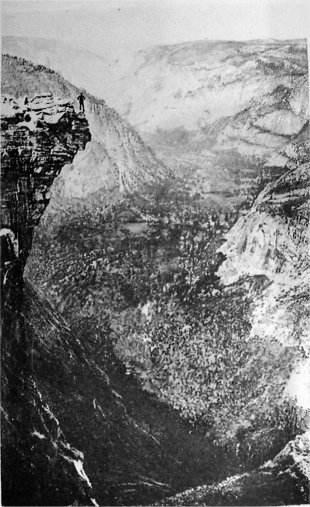

but her association with Watkins must have began much earlier, probably back in 1871. Her stay in the Yosemite Valley during the summer of 1875, when she made her

Half Dome ascent, was also in some way related to her interest in photography (and in Watkins?). Shirley Sargent in her

Pioneers in Petticoats, published in 1966, describes Sarah as

"a San Franciscan who sold Watkins' photographs in the valley". The Half Dome ascent happened shortly after Sally's

31st birthday. Next year, in April 1876, her job description in the San Francisco

Directory is "photographic retoucher", but in March 1877 and April 1879,

she is again "saleswoman with Carleton E. Watkins".

The following, somewhat unflattering description of Sarah was

printed in the New York Tribune in June 1880:

"A brace of female agents of photographic

views infest the hotels [in the Yosemite Valley]. One is well known

to every dweller in the valley by the familiar name

of 'Sally'. She has spent many Summers there,

and great is the power of her tongue. To clinch

a bargain, she will chat, flirt, dance, drive with

you—a most 'amoosin' and versatile girl. The

old resident of the valley remarks to the newcomer,

with a knowing wink, as she passes: There

goes Sally; that gal is the smartest salesman in

Californy. She'll euchre a Jew pawnbroker, and

the way she lays out them English swells is a

caution. She's a credit to the State, and the

valley's proud of her". The reporter also adds: "Sally is a tall, lithe,

remarkably self-possessed young woman, with a

piercing black eye, and a face brim-full of vivacity.

Her rival is a blonde of the 'strawberry'

type, with yellow hair, who wins much custom by

a pertinacity which would put to shame a Niagara

Falls hackman. And how the two rivals do stab

each other's reputations with innuendo and

sarcasm: how they disparage each other's wares

and make bitter gibes on mutual blemishes in

beauty and honesty!" [The use of ethnic stereotyping

in the above segment was by no means an uncommon practice

in newspapers of that time].

In April of 1880, Miss Dutcher runs a gallery connected to Watkins, and

is listed in the San Francisco Directory as

"agent for Watkins' photographic views, 8 Montgomery [street], room 1".

Sarah's name is also shown in the Pacific Coast Directory for 1880-81;

Containing Names, Business and Address, published by L. M. McKenney & Co.,

in 1880: "Dutcher Mrs S L, photographic views, 8 Montgomery".

Actually, she was not a 'Mrs' yet.

During the spring and summer of 1880, her newspaper ads have been appearing in several San Francisco papers daily, for example, in Chronicle

and in Daily Evening Bulletin. Here is an example of her ad from

the San Francisco Chronicle of May 13, 1880, p. 2:

She also paid for a full page ad in the Hawaiian Kingdom (...) Directory and Tourists' Guide, George Browser & Co., Honolulu, 1880. Her newspaper ads stopped running in August 1880, probably because—as

it will be seen below—Miss Dutcher has found a new and different

interest in her life.

There are some uncorroborated

suggestions in Carleton Watkins' biographies of an alleged

romantic attraction—if not an outright liaison—between

him and Miss Dutcher, in spite of (or perhaps, because of!)

a denial

by Watkins in a 1879 letter which he wrote to his wife Frances

shortly after their marriage. What is known is that

Sarah did accompany Watkins on at least one

of his photographic trips to California mountains as late as in 1878. Watkins took several photos of her during that trip to Calaveras Big Trees. One of those photos is deposited in the

California Digital Library

(check the base of the right giant tree!), and another one from the same series, taken inside the Pavillion

built on a stump of a tree, is reproduced in

Carleton Watkins; Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum,

Los Angeles, 1997, p. 79. Miss Dutcher may also be the person on another Watkins' photo at Getty Museum; (download the large size, and check the female figure at the left base of the 'Mother of the Forest' tree). The most frequently used picture of Sarah

(see, e.g., the upper right corner of this highlighted box)

is actually a detail of a larger photo produced by Watkins' Yosemite Art Gallery, deposited now in the Yosemite Museum.

Sarah was not enumerated in the 1870 Census, but in

the Census of 1880, taken in San Francisco in June, Sarah is listed as

"Sarah Dutcher, age 33, single, born in Australia from English

parents, working in a 'photograph gallery', home address 139 Fourth str."

It was not unusual for that era

that people would present themselves in census data somewhat younger

than they actually were. Sarah's true age at the time of

the census was probably 35 or 36, not 33. She was still single,

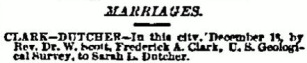

but that was going to change soon. On December 18, 1880,

she married Frederick Clark, a recently appointed full time employee

of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Evening Bulletin, San Francisco, December 20, 1880, p. 3, col. 4

Marriages

CLARK—DUTCHER—In this city, December 18 [1880], by

Rev. Dr. Scott, Frederick A. Clark, U.S. Geological Survey,

to Sarah L. Dutcher.

Another newspaper note a few days later shows them in Hotel Del Monte,

in Monterey Bay, probably on their honeymoon.

Among things that could have brought Sarah and Frederick together, it is easy to identify two:

They both knew and esteemed Watkins, and they

both shared love for mountains.

Sarah clearly was an adventurous outdoorswoman,

and Frederick, in his capacity of a topographer,

had made trips and climbs all over California and the South West.

This was the first marriage for both. Frederick was born in La Porte, Indiana,

forty years earlier. He had worked as surveyor and topographer with

Clarence King, George Wheeler, and Ferdinand Hayden since 1864.

Find more about Frederick Augustus Clark

in the Appendix.

According to the San Francisco Directory of 1881,

"Clark Frederick A., topographer [with]

U.S. Geological Survey, 320 California, room 13" was residing

at San Francisco's Occidental Hotel. Sarah is not listed, but

it is quite possible that she was also living in "Occidental".

A year later, in 1882, Fred Clark has dropped from the USGS payrol, and the Clarks must have left San Francisco. It appears that Frederick took a more lucrative job

in Oakland in 1881 or 1882.

On Dec 17, 1883, the San Francisco Bulletin identifies

him as "Major F. A. Clark",

an "Assistant Division Superintendent of the Central Pacific Railroad in Oakland". An entry in the 1884-85 Husted's Oakland Directory describes Frederick A. Clark as a 'C P R R train master', residing at 909 Peralta street. The same directory may also have signalled that their marriage was in jeopardy: Mrs. Sarah Clark lived alone in a different part of Oakland, at 318 Fourteenth street. Then, in a personal ad that ran in the Oakland Tribune in September 1885, Fred was announcing: "From and after this date I will not be responsible for any debts unless made by myself personally. F. A. Clark".

On December 15, 1885, newspapers in San Francisco and Oakland reported of an impending divorce suit brought by

Frederick A. Clark against Sarah L. Clark. Three weeks later, the Daily Alta California

of January 9, 1886 prints the following short news from Oakland:

"Fred A. Clark has been granted a decree of divorce from Sarah L. Clark".

After five years of marriage, at the age of about 41, Sarah is a divorcee (or a 'widow', which was another term used to describe a divorced woman at that time). Her brother Moses suddenly died a month later. In 1887 and 1888, San Francisco directories show one "Mrs. Sarah L. Clark, widow" (no occupation listed), residing at 222 ½ Fourth street in the City. This may or not have been the former Sarah Dutcher. In any case, that listing disappears in 1889. Did Sarah remarry? Did she move to another region? Did she continue using her skills

in photographic business to earn for living?

What name did she use? Where and when did she die? We may never know.

Her former husband, Frederick Clark, will stay in the Bay Area until about 1904, and

then he will move to New York.

Summer 1876: Anderson in the news. A stairway to the clouds.

1877: Mr Smith goes to... Half Dome

Late 1877: "John Anderson" in the news again. Sheep browsing at the top

of the Dome.

In November 1877, the following sensational and somewhat confusing story appeared in the New York daily newspaper, The Sun. In the article "Above the clouds", Anderson—again called "John" instead of George—is mentioned several times, but only in a supporting role. This time, a pair of sheep took center stage! The content of the article was based on a private letter attributed to Sarah Murphy (Mrs. Andrew J. Murphy). The comments in [square brackets] are mine:

The Sun, New York, Saturday, November 24, 1877, p.2, col.6

Above the Clouds.

Two Sheep Browsing on the Top of the South Dome, Yosemite.

Probably the largest and highest rock in the known world is

the South Dome of Yosemite... a solid rocky loaf, 6,000 feet above the ground.

A more powerful hand than that of a Titan has cut away the eastern part,

leaving a sheer precipice over a mile in height. No man ever trod the top of this dome

until last year. Former visitors gazed in wonder at the

spikes driven into the rock by hardy spirits,

who had repeatedly endeavored to scale it. The

shreds of rope dangling in the wind told the

story of their failure. Last year [true only if the letter was written in 1876],

however, after thousands of dollars

were spent [?!], several persons found their way

to the top of the dome, and this summer [1876?] two sheep were discovered

browsing on the hitherto inaccessible peak. Mrs. A. J. Murphy,

the wife of a late hotel proprietor in the valley, writes

to a lady in this city as follows, under

date of November 11 [1876? 1877?]:

John[!] Anderson is building stairs up to the top of the South Dome.

You can go up now by holding on to a rope, but it is quite a tiresome trip.

A few ladies in the valley have made the ascent, and I am sorry I did not

attempt it. But I am one of the few who have seen the sun rise

on the top of Cloud's Rest, and its glory will never fade from my memory.

[Snow Register shows that Mrs. Sarah Murphy made this trip to Clouds Rest and beyond in August 1876].

Strange to say, two sheep found their way to the top

of the South Dome this summer, a dam and her lamb. How they ever got there

is more than any one can tell. They found bunch grass and shoots to eat,

but no water—only the dew that fell on the dome at night. Anderson was

going to carry them up some water when I left ...

The rest of the article covers some other events in the Valley. See the full transcript from The Sun on a separate page.

It would be appropriate to add a few clarifications here. Most of the events mentioned in the article can be traced back to 1876. Yet the article was published in late November 1877. Why such a long delay? The editor provided no explanation. The Sun's chronology of past attempts to climb the dome is perplexing. For example, there was no acknowledgment that Anderson was the first to succeed. It was also suggested that "thousands of dollars were spent" on conquering the Dome. Where did this information come from? Since Mrs. Murphy's letter has not survived, we don't know which parts of the article were written by her and which were provided by the Sun's editor.

The Murphys didn't stay in Yosemite much longer. Indeed, late in 1876, A. J. Murphy gave up his ten-years lease of a hotel in the Valley. He and Sarah moved to Mammoth City, and then to Bishop, in the Eastern Sierra.

A. J. died there in 1907, and Sarah died two decades later (1927), perhaps never fully aware of the popularity and wide circulation that her private letter to a New York friend had once achieved.

It didn't matter that

the most sensational part of the article, the tale of a dam and her lamb must have been someone's silly joke that was successfully "sold" to Mrs. Murphy. The newspaper owners, editors and readers loved that part, and no one questioned its validity at the time. Over the next five months, the story was reprinted many times across the country. Then a much shorter version appeared, focusing solely on the adventurous sheep, but making no mention of Anderson or Mrs. Murphy. This mini version of the original article served for at least another eight years as a convenient 'filler' in newspapers, during seasons when more substantial topics were lacking.

Surprisingly,

even James M. Hutchings, in his book In the Heart of the Sierras (1886),

seems to give some credence to the Sun's story. In his chapter on Half Dome, he wrote: "Two sheep, supposed to have been frightened by bears, once scrambled up there; to which Mr. Anderson

daily carried water, until they were eventually lost sight of. Their bones

were afterwards discovered side by side, in a sheltered hollow".

However, if you are among those who have climbed the Dome, by any route, you know that it would be impossible even for a mountain sheep to reach the Half Dome summit, let alone a domestic animal (and a lamb!).

Still, be aware that some small animals (with big appetites!) live on top of the Dome: lizards, ground squirrels, wood rats, pikas, and even yellow-bellied marmots have been known to make their homes there.

1878:

Lady Gordon Cumming: How to do it properly

Lady Gordon Cumming, quoted already above, describes technique used

in early Half Dome ascents in a letter

reprinted later in Granite Crags (1884). On Saturday,

May 4, 1878 (Chapter VI, in her book), she wrote [emphasis mine]:

Having thus made the ascent a possibility, Anderson's delight

now is to induce enterprising climbers to draw themselves up by his

rope ferry, the manner of proceeding being to keep one foot on

either side of the rope, and, retaining a good grip of the rope

itself, gradually to haul one's self up to the summit, there remain

for a while lost in wonder at the grand bird's-eye view, and then

climb down backwards.

It is all right

so long as most of the stanchions stand firm and the rope

does not break; but should this simple accident occur, there would not be

the faintest possibility of rescue; indeed, it would be no easy task

to recover the battered and mutilated remains of any poor

wretch who might fall from that

majestic dome. A leap from the summit of St. Paul's would be child's

play in comparison. A man troubled with suicidal mania would find it hard

to look down from a precipice a sheer fall of 5000 feet, and resist

the temptation to cast himself down...

Two months later, on July 12th

(Chapter XIII), she adds:

George Anderson, [who is] regarding

the giant [Half Dome] with all the pride of a conqueror, frequently

invites me to ascend [it] under his able guidance, but which

I consider as a feat too dangerous to compensate for the risk...

And indeed, she left the Valley without ever climbing the Dome.

1878: Oxonian, Botanist, Astronomer

Ascender: Arthur Clarke (June 29, 1878)

In May of 1878, Walter G. Marshall left England for a three-months trip

to the United States. One leg of the trip was to be a visit to Yosemite Valley.

Marshall didn't go alone. With him, aboard the Cunard

steamship "Scythia", and throughout the journey,

was one of his college friends. Marshall's 1878 trip, as

well as one of his later visits to the United States, are described

in his book published in London in 1881, under the title

Through America. An account of a trip

from San Francisco to Yosemite, June 20 to June 30, 1878, is given

in Chapters 16-19 of the book.

It contains a segment that is particularly interesting for the present work:

Marshall's friend, who is only identified as "C——",

climbed Half Dome on June 29, 1878.

It took some detective work to establish true identity of

Marshall's adventurous friend. In the first chapter of the book,

Marshall introduces him as "my college friend C——",

but he carefully avoids revealing anything else about "C——",

as if the friend had insisted to remain anonymous.

Instead, on hundred pages in the book, he

is simply referred to as "my friend" or "my fellow traveller".

However, towards the end of the book, in a single paragraph, Marshall (perhaps by mistake?) reveals his name: The companion was one "A. N. Clarke".

There is another independent evidence to support that disclosure.

Port records from New York confirm that "W. G. Marshall, age 25,

gentleman", and "A. N. Clarke, age 25, student", shared a cabin in

"Scythia". Marshall had studied at Winchester College, and at Oxford.

I didn't find any student with the name "A. N. Clarke" at Winchester,

but a check of the

book Alumni Oxonienses was more successful: Mr. Clarke, from Leeds,

got his MA at Oxford the same year as Marshall (1875), and his full

name was Arthur Noble Clarke.

Marshall briefly describes circumstances related to Clarke's ascent,

then allows Clarke to give a detailed first-person account of that

climb. Here is a segment from Marshall's book that was written by Arthur Clarke:

Through America; Or Nine Months in the United States,

by W. G. Marshall, London, 1881, Chapter 19, pp. 380-383:

[abridged]

Leaving Bernard's [Barnard's Hotel]

on foot at 10 a.m., I reached Snow's at 12.10 p.m.,

had luncheon there, and remained till 1.30. Then, mounting to the top of

the Nevada Fall, I struck off by a trail to the left, which led me over a

shoulder of the great South Dome till I came to the foot of a

conical-shaped rock, called the Little Dome, which I found I was obliged

to climb... This successfully scaled, I had to

descend again... to a dip between the two Domes, the huge granite mass of

the South Dome now looming majestically

above me. The rope of the Scotchman now appeared to view, running down

straight for 960 feet from the top of the curve, close to the vertical

face of the mountain... The sections of this

rope are not all equal, some being not more than twenty feet in length,

while one or two sections near the top of the curve are nearly 100 feet in

length, and, being quite loose, thus oblige one to describe a considerable

arc. Where the sections are short you go up like a monkey, hand over hand,

close to the rock. The lower portion of the precipice was very steep,

having an angle of 10 degrees from the vertical, and this part had to be

ascended

without any rest. From this point the grand curve of the Dome began, the

granite lying here and there in immense overlapping,

concentric slabs—like gigantic armour-plates,

the 'plates' in this case being three to

five feet thick, difficult to climb over, even with the aid of the

rope. Over these I had to scramble as best I could; but there were a few

cracks in the granite which enabled me to obtain an occasional foothold,

and, leaning with my back against the almost vertical wall of rock, rest

awhile and contemplate the view...

The gymnastic performance now began to get easier as to the grade; but

the fatigue caused by the rarity of the air, and the heat of a blazing

Californian sun, glaring as it did directly in my face, caused me to

inwardly rejoice when I reached the summit. That this is a much less

difficult—though not the less dangerous—climb than it looks,

is certain,

and provided the soundness of the rope be guaranteed, a lady can without

difficulty make the ascent. But her chief embarrassment would be the

'monkey' performance, if she went up in ordinary attire.

Having rested for a few moments on the top of a stony couch...

the next thing to do was to quench

thirst, which had become simply unendurable. To this end I made my way to

a small snow-field lying about 200 yards off. Then I devoted an hour to

the view, sitting down on the edge of the precipice and dangling my legs

over, having first lit my pipe that I might enjoy the view the

better...

The descent I found considerably easier than the ascent, for the rope

had now been fully tested, and all that it was necessary to do was to

cling firmly to it, and let myself down hand over hand...

At Snow's... I was given a tallow candle, to light if it should get too dark

during my descent into the valley. But it was not brought into

requisition, for I reached Bernard's[!] at 8.18 p.m., having been away from

the hotel just ten hours and eighteen minutes.

This was an excellent total time for a day hike on foot from the Valley,

considering many stops that Arthur Clarke made along the way.

Read Marshall's introduction and the complete text of Clarke's well written and

interesting description of his Half Dome adventure.

Arthur Noble Clarke (1851-1912), the eldest son

of Dr. Thomas Clarke ("physician, surgeon, and apothecary"),

was born in December 1851 in Leeds, Yorkshire. He had three younger

siblings: George E. Clarke, Florence L. Clarke, and Bernard L. Clarke.

He enrolled in Wadham College, Oxford University, in November of 1870,

studied natural sciences, and got his BA in 1875, and his MA in 1877.

During his visit to Yosemite with Marshall, he was 25 years old.

According to British census data,

in 1881 he was in London, studying medicine.

In the late 1880s, he helped putting together two essays

that his father had written

("The Fate of the Dead", and "What is the Soul? and what becomes of it?")

Arthur was registered in the 1911 England Census while living in Eastbourne district, in Sussex. He was

probably still unmarried. He died a year later, on Feb 28, 1912, in London.

Ascenders: John Lemmon, E. W. Baker (August 14, 1878)

John G. Lemmon was a noted California mountaineer, and a self-taught

botanist. Here is a fragment from a trip report describing his

Half Dome adventure. Full report

is also available.

Lemmon, together with John B. Lembert (Lemmon calls him "Lambert")

had reached the foot of Anderson's Half Dome route. Lemmon was

slightly injured earlier in the day when he fell from his horse,

and he didn't think he would be able to continue up the ropes.

They were ready to return back to the valley, when another man appeared...

Pacific Rural Press, September 14, 1878, pp. 162-163

Scenes in the High Sierra back of Yosemite.—No. 1

(Written for the Press by J. G. Lemmon).

...My regret at being placed hors de combat just

that morning, of all the 10 weeks almost constant riding from Santa

Barbara to and about Yosemite, now became agony. I gathered souvenirs of

flowers and prepared to return, when a voice hailed us from over the east

dome, and a man came stalking down the slope with a sure and easy tread

that told the strength of his limbs and the resolution of his heart. He

proved to be Mr. E. W. Baker, a cool headed carpenter from Alameda,

accustomed to walking on dizzy heights. Hastily inquiring he learned my

state, but declared I must go up with him if he had to carry me on his

back. Taking from a bush near by the rope that Anderson used for the

purpose, about 15 feet long, he tied one end about his waist and I placed

the other about mine.

Promising to let me down from any point if my strength failed me, he

grasped the rope and ran up nimbly as a cat, hand over hand, and I slowly

followed. Raising the rope out from the rock causes your pressure against

it with nailed boots to be increased in the ratio of your lifting

power. So firmly your feet cling to the glassy rock, and clink, clink, the

iron nails ring out upon the air, keeping time with the regular reaching

of the hands up, up, up!

Occasionally, clefts in the rock afforded foothold enough for a moment's

rest and a survey of the glorious

scenery unveiling below... [Way below, from the

attendant dome] the voice of Lambert came

cheerily: "You are doing well!" "About half-way up!" Later came the

shout, "Three-fourths of the way!" My back seems to be separating in the region

of the lumbar vertebra and pains shoot through the part keen as

knife-thrusts, but I keep on grasping the rope with trembling,

weakened fingers. "Only three pins more!" I gasp and feel an inclination

to halt, and turn around giddily. "Depend more upon the little rope,"

Baker calls down, in a firm voice, "I can pull you up bodily." "Almost

up!" shouts Lambert from the far depths. "One more pin!" Baker creeps up to it,

sits down above it, and pulls me up over the cape stone. The perilous

climb is done; the crown of "Tis-sa-ack," is reached, over 10,000 feet,

nearly two miles above the level world! Rest followed, while the hearts

throbbed and the eye wandered. O, what a glorious vision lies out-spread,

of gorge and dome, turret and pinnacle!

Exploring the top of the half dome, we found it a convex,

elliptical table of rock, depressed several feet near its center by a

cross valley, and extending about 100 rods in a direction nearly northeast

and southwest. The north wall, seemingly so smooth and clean cut from

below, is really notched and much diversified. On its outer point, the

visor of "Tis-sa-ack's" crown, stands a flagpole of fir about 15 feet

long, and eight inches in diameter at its base, upheld by piled

rocks. Though seldom registering myself in the usual places, I thought it

proper to pencil my name here with the thirty or forty only others that

have ventured up this fearful steep... Only one tree has taken

root on the summit. This stands near the edge at the western side of the

ellipse and is about two feet thick at base and 25 feet high, with the

peculiar, many-branched, depressed limbs of the Pinos monticola

found on such highths...

The descent of "Tis-sa-ack," by the small rope

swinging almost vertically over the side, was scarcely less fearful though

taking less time, and was performed by backing down. Often the foot failed

to find a resting place and you dangled in air until reaching over and

beneath the concentric layers your iron boot-nails caught upon the inner

rock...

(Read the complete article from the

Pacific Rural Press).

Lemmon's trip to the top of Half Dome is mentioned directly or indirectly

in several other sources, for example:

Report of the Botanist, J. G. Lemmon, in

Second Biennial Report of the California State Board of Forestry for the Years 1887-1888, Sacramento 1888.

pp. 84-85:

...But few have enjoyed what it was the writer's privilege

to experience while exploring the upper heights of Yosemite.

I climbed Anderson's rope

(now both the rope and its intrepid maker in dust)

to the top of South-Half Dome. Exploring its crown we found

an ellipse of table rock about one hundred rods long,

with but one tree maintaining its hold, as by an eagle's

talons, to the wind-swept rock, two miles in vertical

above the sea. Of course, it was the Limber-twig Pine [Pinus flexilis],

over two feet thick at base, but only a few in height,

with willowy branches that receded and swayed, self-protectingly,

with every breeze...

After Lemmon's death in 1908, his collection of California plants and

specimens, known as "Lemmon Herbarium", was transferred from Oakland to

Berkeley, and many items were examined and listed in Prof. Smiley's

book about the boreal flora of the Sierra. In the section about

Rosaceae, subsection Holodiscus dumosus (p. 231),

the author talks about various samples of spiraea shrub that he had examined

while preparing the book, among them one specimen

that was collected on the "summit of Half-dome,

Yosemite, by Lemmon, on August 19, 1878".

(See, A report upon the boreal flora of the Sierra Nevada of California,

by Frank Jason Smiley, U. C. Publications in Botany,

Vol. 9, University of California Press, September 1921, p. 231. Note that Lemmon dates his Half Dome visit on August 14, not August 19, see his article in the Pacific Rural Press).

More about the events that had brought

the botanist to Yosemite in 1878, can be found in

California's Frontier Naturalists, by

Richard G. Beidleman, University of California Press, 2006.

One section of the book is devoted to

"J. G. Lemmon and Wife" (pp. 415-429). Beidleman's research reveals

that in June 1878, Lemmon had arrived to Santa Barbara to

"join a lengthy excursion to Yosemite". The party was to include several

locals including Sarah Plummer, Lemmon's future wife. However,

in the end, "six campers went, but Sarah was too weak to join them".

We don't know who else, besides Lemmon, was in that group of "campers",

but we know that Lemmon was the only one from that group that

had reached the top of the Dome.

John Gill Lemmon, (1832-1908), was born in Michigan,

and arrived to California in 1865, to recover from injuries sustained

during the Civil War. He became interested in botany, and because of his

mountaineering skills, was able to discover many new species of plants

in remote parts of the Sierra. He was 46 years old when he climbed Half Dome.

Two years later, in 1880, he married Sarah Allen Plummer,

who would accompany him on many trips along the Pacific Coast, in the Sierra,

and in the Rockies. From 1888 to 1892 the couple worked for the

State Board of Forestry, John serving as botanist and his wife as artist.

In the 1890s, Sarah promoted the bill that eventually made the golden poppy

California's state flower. Mt. Lemmon in Arizona is named after her.

John died of pneumonia in Oakland, in 1908, and Sarah died in Stockton in 1923.

They are buried in Mountain View Cemetery,

Oakland, California.

I could not positively identify E. W. Baker. A

photographer, Ellis W. Baker, worked in the Alameda county in the late

1870s, but according to Lemmon, his companion was a "carpenter

from Alameda", not a photographer.

Ascender: William Pickering (late Summer, 1878)

A note in the Appalachia,

Boston, Vol. 2, No. 1, June 1879, p. 93, describing previous year's

activity of the Appalachian Mountain Club, says:

"On December 11, 1878, at the Seventh Corporate Meeting,

Mr. W. H. Pickering read a paper describing an ascent of the

Half Dome, in the Yosemite Valley, illustrated by views of the Valley

and its special points of interest".

The note was referring to William Pickering,

one of founders of the Appalachian Mountain Club,

and later a noted astronomer.

The lecture was describing his "recent" trip to Yosemite,

perhaps in 1878, but a precise date of the ascent was not given.

While Pickering's original report is

probably lost, the following autobiographical note in MIT

Technology Review has a few sentences about that climb:

Technology Review, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

Cambridge, Vol. 18, 1916, p. 307:

...I had always been fond of mountain climbing, and among

other things ascended the Half Dome in Yosemite Valley by means of a rope.

For 900 feet the ascent had to be made hand over hand, supporting a

considerable portion of my weight at the same time on my feet.

The ascent was continuous, as there were no intermediate ledges on which one

could rest. In fact, the only ledges were inverted!

Comparatively few living persons have

been on the summit, since the rope was removed many years ago.

When William Pickering died in 1938, several of his friends

recalled his Half Dome climb. In an obituary, in

the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific,

Vol. 50, No. 294, pp.122-125, 1938, Leon Campbell wrote: "Professor Pickering was a

great traveler and mountaineer... He not only scaled the heights

of Half Dome in the Yosemite, and El Misti in Peru, but also one hundred

other peaks in various parts of the world". E. P. Maartz, Jr., wrote

in another obituary: "In 1928 Professor Pickering made a trip to southern

California and this proved to be his last to that region... One thing he

was most eager to do... was to revisit the Yosemite Park. He had been

there once before, fifty years previously, in 1878, as a young man of twenty;

and on that occasion had climbed the Half Dome. He was one of the first

men to do this, and one of the very few who climbed the Half Dome

at all before the iron spikes and chain guards were installed...

He was a great climber in his younger days, and was always a lover of

the mountains and the great outdoors..."

(Popular Astronomy, Vol. 46, No. 6, June-July 1938,

pp. 299-309).

The above text confirms 1878 as the year of the climb.

In late July that year, William traveled to Cherry Creek, near

Denver, Colorado, to observe that year's total eclipse of the sun (July 29).

California newspapers then report his arrival to San Francisco

on the overland train on August 6, 1878. He was accompanied by

his sister-in-law, Lizzie (Mrs. Edward C. Pickering). It looks like that they have stayed at the West Coast for about a month,

and then, on their way back to Boston,

made a stop in Cincinnati on September 13.

This further narrows down the dates of William's visit

to Yosemite and Half Dome to the second part of August

or to early September of 1878.

William Henry Pickering (1858-1938),

was 20, and still a student at MIT in the summer of 1878.

Later that year he published a note on his observation of

the eclipse with two polariscopes and a polarimeter in the

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society,

London, Vol. 39, No.2, December 13, 1878, pp. 137-139.

William stayed at MIT as staff after graduation in 1879,

but later worked at Harvard Observatory,

where his older brother Edward was Director. In 1884,

William Pickering married Anne Atwood, and two of their three

children survived him:

William T. Pickering (born 1887, died in Los Angeles, in 1952)

and Esther Pickering, later Mrs. Murton S. Harland (born 1889, died in

1987 in Alberta, Canada).

In August of 1898, W. H. Pickering took a series of photographic images of Saturn at

Harvard's Arequipa Observatory, in Peru, and

discovered Saturn's ninth moon Phoebe (the work was published in March 1899).

He was the author of many articles and books on astronomy.

He died in Mandeville, Jamaica, in January 1938, where

he lived since 1911, and where he had his private

astronomical observatory.

1879: Brave clergymen

Ascenders: Asa Fiske, John Allis, many others (June 12, 1879)

Congressional tourism is not invention of our days. From June 7

to June 15, 1879, a Yosemite Sabbath-School Assembly was organized,

and newspapers reported huge interest among clergymen for the meeting.

Delegates from 23 states attended.

Just in one train coming from the East there were "one hundred

and sixty-five of the party who intended visiting the great valley"

(Daily Evening Bulletin, July 4, 1879, p. 4).

The "Union Chapel" in the Valley was dedicated on this occasion.

Galen Clark and John Muir made presentations to the assembly.

Muir's speech about glaciers "inspired the crowded house with

such enthusiasm that more than a hundred climbed the trail to

Upper Yosemite Falls with the lecturer". (Daily Evening Bulletin,

July 12, 1879, p. 2). Some of attendees were even more adventurous:

Daily Evening Bulletin, June 14, 1879, p. 3

Yosemite, June 14th.

...Excursions, semi-scientific and pleasure, are the order of the day.

Rev. A. S. Fiske has led two parties of climbers to the summit of

South Dome. Rev. J. M. Allis of the Occident has also made this ascent...

Fiske and Allis were Presbyterian ministers in San Francisco

at the time of the Assembly.

Asa Severance Fiske (1833-1925),

was about 46 years old when he made the ascent(s?) in 1879.

He was born in Ohio, graduated in class of 1855 at Amherst College,

and served as chaplain for the Fourth Minnesota Infantry during the Civil War.

After the War, he held pastorates successively

in Rockville (Connecticut), Rochester (New York), San Francisco, and

Ithaca (New York), until he was eighty-four. He died in New Orleans.

John Mather Allis (1839-1899), was 39 in the summer of 1879.

Born in Quebec, Canada, he left for Troy, N.Y., at the age of 14.

He graduated from Princeton in 1866, and from Union Theological

Seminary in 1869, then served in Albany (New York), Lansing (Michigan), and Anaheim (California).

Between 1877 and 1881 he served

at the Larkin Street Church in San Francisco.

After a brief stay in Lafayette (Indiana), he got appointed a foreign

missionary and assigned to Chile, where he died.

1879: New York Tribune correspondent

Ascenders: George H. Fitch, W. Henry Grant, Henry D. Robinson (July 18, 1879)

In July 1879, an unnamed San Francisco correspondent of

a New York paper made a trip to Yosemite Valley.

There, he encountered two Eastern men, who—like him—had

a prejudice against riding over the trails. They "struck

hands, and formed a compact to do the place on foot".

Their adventure in Yosemite was described a year later in the

New-York Tribune:

New-York Tribune, June 27, 1880, p. 5

Ten Days in Yosemite

(From an occasional correspondent of the Tribune)

(...)

A Perilous Climb On South Dome.

We essayed first the easier trails—those to

Glacier Point and the Vernal and Nevada Falls—and

by the third day felt equal to more ambitious

efforts. So we laid siege to South Dome—a peak

which has a bad reputation, and which was wholly

inaccessible until a few years ago. It is shaped

like a sugar-loaf, sliced in half, the smooth flat side

being toward the valley. The trail winds about

the base, makes an immense detour, and emerges at

the rear of the mountain. It is thickly wooded

until it approaches the summit. Then trees and

vegetation suddenly disappear; nothing is left but

barren rock, looking like great masses of iron

welded together, and seamed by overlapping folds,

which give the mountain crown a close resemblance

to the flank of a mammoth rhinoceros.

The summit rises directly from a narrow plateau,

on which a place is soon reached where the trip

ends for the lazy or timid. The path slopes away

on either side, in long roof-tree style, for

a thousand feet, then falls in a sheer precipice

of three thousand feet to the valley below.

Up the steep crown of the mountain, 900 feet in

perpendicular height, which makes a spherical

angle of about sixty degrees, is stretched a rope,

formed of seven strong hemp ropes of the size of an

ordinary clothes-line, knotted together at intervals

of eighteen inches. It is fixed to the rock by iron

staples every fifteen or twenty feet. The only

danger lies in the giving way of a staple or the

breaking of the rope, two casualties that could not

readily occur, as the rope is frequently inspected by

guides, and the staples seem to be clenched on the

nether side of the mountain. To an active man or

woman, not given to dizziness, the ascent is without

much danger. Carefully working one's way

hand over hand, the slack of the rope allowing a

nearly upright position, one finally nears the summit

and skips over the last one hundred feet by the

aid of a single line.

A barren plateau of several acres is the foreground.

The entire length of valley and can[y]on

stretches away in front, so near that it seems you

may call to the pigmy figures moving about a mile

below you, and two miles away as the bee flies.

Directly below, as you lie prone on the rocky ledge

and peer over, is Mirror Lake looking like an

artificial fish pond. On the left is the Little Yosemite

Valley, with a spray-like fall in the dim distance,

and at the back the shaggy-headed monster whose

fastnesses are seldom disturbed is Cloud's Rest.

Mountain peaks can't be enjoyed long, more's the

pity. Ten minutes on a mountain top for a five

hours' tramp is usually the rule. But in those

minutes one may get a view of the valley which is

unsurpassed from any other point...

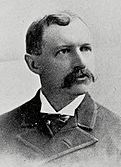

Wm. Henry Grant in 1878,

while studying sciences

at UPenn.

Twenty-two years after

the ascent: Geo. H. Fitch

on a 1891 photo.

At first it looked as if the anonymous author of

the article and the names of his climbing companions would forever remain

unknown. But further research unearthed a strikingly similar article, just much shorter, in the Scribner's Monthly, New York (thank you Google!) This time, however, the author had disclosed his name: George H. Fitch. It was then easy to confirm that George really was a New-York Tribune West Coast correspondent. In the abridged version Fitch didn't explicitly describe the Half Dome ascent, but he mentioned that the trip up the Dome happened on July 18, 1879. The next task, finding the names of his two partners, was completed when I had a chance to check the register of Snow's La Casa Nevada Hotel (aka "Snow's Register"). The hotel was a convenient stopover for travelers to Half Dome, Cloud's Rest or the Glacier Point. Our three climbers indeed signed up in the Register, and Fitch's two 'Eastern men' turned out to be H. de G. Robinson (New York-San Francisco) and W. Henry Grant

(Philadelphia). George Fitch kept track of his expenses for the trip from San Francisco to Yosemite and back. In those 12 days he spent a total of $123, with two largest items being the round fare by Madera route, $59 (railroad and coach), and board in Yosemite Valley for 10 days, $30. Two of the three climbers would achieve notable careers later in life, while the eldest one ended up living a quiet and unassuming life north of the border. I wonder if they had stayed in touch? Perhaps Google will reveal even that one day.

William Henry Grant (1858-1933), born in Philadelphia, was one of 10 children in the family of Charles and Emma (nee Collier) Grant. He obtained his Certificate of Proficiency in Science from the University of Pennsylvania in June 1878. Shortly after the Commencement, he left his home town for a year-long employment in San Francisco, where he worked in the West Coast office of the Philadelphia's merchant firm "George M. Grant & Co." (George may have been his eldest brother). Towards the end of his California stay he made the trip to Yosemite. He was 20 at the time of his Half Dome ascent. Upon return to Philadelphia he studied literature for a year, and then followed various mercantile and banking pursuits. It appears that he didn't find full satisfaction in any of those vocations. In the early 1890s his interest shifted dramatically. He found his new calling by working as a lay person in foreign missions. In the next fourty years he would travel extensively, visiting or organizing Protestant missions around the world. He held high positions in several American and Canadian Mission Boards, and he played a substantial role in the creation of the Canton Christian College, China. He left a prolific opus of articles on missionary causes in newspapers and magazines. When he died in New Jersey in 1933, at the age of 74, an obituary described him as "one of the most gentle and modest of men, and at the same time one of the most efficient and creative personalities of our time".

George Hamlin Fitch (1852-1925) was destined for success. A valedictorian in his grammar school, talented orator, popular student and a co-editor of a student paper at Cornell University (class of 1875), he became an assistant editor of the New York Tribune shortly after graduation. He arrived in California on May 30, 1879, and landed a job with the San Francisco Chronicle. Several weeks later, he and two companions would make their trip to Yosemite. He was 26 at the time of his Half Dome ascent. For the next several decades he would work at the Chronicle as a journalist, a night editor and finally as an influential literary editor. In 1881 he married Theodosia Hudson, a sister of Chronicle's city editor, and they had two children, who would later attend Stanford. Apart from the Chronicle, George Fitch was also writing articles for magazines of the day, and was the author of several well received books. By the turn of the century he was at the top of his professional career, but a downturn in family affairs would follow soon. His daughter left home and went through several childless marriages. George divorced Theodosia before 1906, and then his beloved son Harold suddenly died at the age of 25 in 1910. At that time, Fitch was just completing what would become his most popular work, "Comfort Found in Good Old Books". The first edition of the book features a touching tribute to Harold in the opening paragraphs ("...my best critic, my other self, whose death has taken the light out of my life.") In 1911, he took a 7-months trip around the world. In 1912, George remarried, but abandoned his new wife after only three months. In 1915, he left his job at the Chronicle, moved first to the East Coast, and then made a trip to Europe hoping to become a war correspondent from France and Belgium, but he didn't get a consent from British military authorities. He then spent some time in New York and possibly Florida. After 1915 he never again had a permanent address, and the only way to get in touch with him was through his San Francisco lawyer. In the last few years of his life he apparently moved to southern California. He suddenly died in Arcadia in February of 1925, while waiting for an interurban streetcar. Through the efforts of his daughter Mary (Marian), the last surviving member of the family, they all are now reunited once again: George, Theodosia, Harold and Marian share the same lot at the Cypress Lawn cemetery in Colma.

Henry De Groot Robinson (~1840-1906) was the eldest of five sons in the family of Francis and Anne (nee De Groot) Robinson. Henry's father was a well-to-do wholesale coal merchant in New York. Henry's mother descended from a prominent New Jersey family of Dutch origin. In about 1876, Henry moved to California, perhaps to gain some experience in financial affairs. For several years he worked as a bookkeeper in the Nevada Bank of San Francisco. He was 39 at the time of his 1879 Half Dome ascent. By the end of that year, he is back in New York, where he was employed in his father's dealership. A bachelor, he was still living with his parents at the time when all his younger siblings were already married. That changed in a few years, when he met Miss Florence Bush. She was a daughter of John T. Bush, a Buffalo lawyer, businessman and for a time a member of the New York State Assembly and Senate. In 1866, Mr. Bush had purchased a huge estate in Clifton Hill, on the Canadian side of the Niagara River and Falls, and erected a spacious mansion there. Henry (43) and Florence (35) got married in 1883, in a town near the Bush estate. Henry kept working in New York until about 1886, and then the couple relocated to Ontario. The 1891 Canadian Census finds Henry and Florence in Niagara Falls (township), living in the Bush mansion. Florence died in 1898, and Henry in 1906. Both are buried in a small church cemetary in what is now the City of Niagara Falls, Ontario.

1881: Old rope disintegrates

According to the following accounts,

Anderson's rope became so frayed and unsafe

by the summer of 1880, that its lower part got cut to prevent any further

climbing attempts and possible accidents. However, some adventurers

were still not discouraged.

Ascenders: Anderson, George Strong, possibly another person (second part of May 1881)

This is an abbreviated version of George Strong's description of

his ascent of Half Dome in the spring of 1881. Check also the

complete article, with illustrations

on a separate page.

Pacific Rural Press, San Francisco, Saturday, June 18, 1881, p. 431

In October 1875, Mr. Geo. G. Anderson succeeded, after two days and a

half, in accomplishing the first Half Dome ascent. Mr. Anderson is a Scotchman, who has resided in the valley for 15 years. He is a ship

carpenter by trade, and had followed the sea in that business for many

years before settling on shore. Before his residence in the valley, he was

engaged in putting up one or two suspension bridges over the Tuolumne and

other rivers, and acquired considerable local fame for fearlessness and

steadiness of nerve. After determining to try the ascent of the dome, he

prepared eye-bolts, drills, chisels, and the necessary ropes, and packed

them to a convenient place, and after much hard work he reached the top,

and planted a flagstaff there.

Last year the rope became unsafe, and was cut to prevent any further

attempts and possible accidents. When Anderson offered to accompany me to

the Saddle, which he said was as far as we could go, I eagerly accepted

the invitation. We followed a comparatively easy path toward Cloud's Rest,

until we reached a point where we turned off and commenced the ascent

toward the Dome. We passed the cabin where Anderson lived and

prepared the iron work and bolts for his attempts, emerged from the timber

and caught the first glimpse of the Dome and the Saddle. We climbed the

projecting spur of the Saddle, with considerable difficulty, and took a

long rest upon the comparatively flat surface at the top of this

elevation. Two hundred and fifty feet or more above us dangled the frayed

and ragged end of the rope which had been broken at that point, and after

extending, with one or two breaks, some 400 or 500 ft upward, it again

terminated, and apparently where it would be most needed.

I had made up my mind before starting that, if possible, I would attempt

the ascent, but dared not speak of it to Anderson, fearing that he would

not allow it. But Anderson now seemed to divine my intention. He gathered

a few of the bolts which had been pulled out and were lying at the foot

upon the Saddle, and selected some of the best of the pieces of rope

which were still lying there, to repair with. We started up, putting in a

bolt here and there, and making the rope fast, for it was almost entirely

loose from the point where it commenced, to its upper end. We added some

rope at the lower end, and worked slowly up, not trusting the rope, as it

was very weak in many places. Before we had accomplished half the ascent,

the clouds began to close in around us, and we abandoned the rope and went

up the remainder of the distance as fast as we could. We found the

flagstaff fallen down, and set it up, and then the clouds broke away a

little and gave us a magnificent view of the valley.

G. H. Strong in the mid 1870s.

As new ropes have been sent to the valley by the commissioners, the South

Dome will soon be again accessible to anyone who has nerve and does not

mind a little hard work, and it is probable that by another season a

flight of steps will be put up, as Mr. Anderson has all the necessary

lumber just at the foot of the Saddle, and well protected.

I couldn't find any confirmation that a new rope had been delivered and

mounted in 1881. It appears that other parties during 1883 (below), still found

the rope quite weather-worn, with many staples loose and detached

from the rock.

George Henry Strong (1839-1925),

was about 42 when he climbed Half Dome with Anderson. He was

born in Massachusetts, but moved to San Francisco

after graduation. He was a patent attorney (solicitor) in the City,

and an avid sportsman: a member of the oldest boat club in the Bay Area

(Pioneer Rowing Club), and one of founders of the

San Francisco Bicycle Club in 1879. He was a co-author of a biking book,

The Cyclists' Road-book of California: Containing Maps of the Principal

Riding Districts North, East and South from San Francisco,

published in

1893. He was also connected with Dewey & Co.'s Mining and Scientific Press

Patent Agency, and a member of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

His younger daughter, Lilian, became the wife

of Edward Hale Campbell, a Vice Admiral of the U.S. Navy, in 1899.

In his later years, George lived in Oakland, with the family of his

older daughter Georgie Strong Hubbard. He died on June 1, 1925.

1881: Deaf and mute teacher

Ascender: Douglas Tilden (June 21, 1881)

An anonymous correspondent of the Indianapolis News, identified only by initials W.A.C., described a South Dome ascent that happened in mid June of 1881. A party of three men took a train from Oakland to Stockton, where they spent a night in a hotel. By noon of the next day they reached Milton, which was as far as they could go by rail, and then took a stagecoach for Sonora. In this town they acquired three saddle horses and a little donkey

to carry their provisions, and entered upon their several-days, 65-miles camping out trip to Yosemite Valley. Their route led them over the Tuolumne River to the Oak Flat Road. At that time, the highest point of the road was close to Tamarack Flat. From there, a steep and narrow stagecoach path [no longer passable] brought them down to the Merced River. The donkey had been slowing their progress, but became a center of attention once they reached the Valley. A photographer even offered them free photos of their party in exchange for the privilege of taking a picture of the donkey alone. [There is more on that photographer below]. In the next several days they made shorter hikes from and around the Valley, and then they focused on the majestic South Dome. It didn't take long before one member of the party, whom W.A.C. calls 'Truthful James' on account of his family relationship to the poet Bret Harte, declined to attempt the ascent. The other two were undounted. Here is a description of the events that followed:

Indianapolis News, July 21, 1881, p. 2

...For many years after the discovery of the valley all attempts at scaling the Dome were unsuccessful, and, if I am not mistaken, attended with the loss of several lives. [The author is wrong here; there were no deaths related to any of the Dome ascents in the 19th century]. The visitor now, who wishes to take this trip, goes to the eastern side of the mountain [by way of Vernal and Nevada falls], and after climbing over two smaller domes finds himself at the base of the third, with several hundred feet of rope between him and the summit... [The two of us] went as far as we could on our horses, and left them near the first of the small domes. We then proceeded eagerly on foot to the rope. We experienced some difficulty in breathing, but my companion, a deaf and mute teacher named Tilden, did not pause long before seizing the rope, and soon passed out of my sight over the curved surface of the dome. Then I gathered the ragged ends of my courage together, set my feet against the rock and began walking up the steep incline. I proceeded with marked success for about two hundred feet, when I stuck my toe into a crevice of the rock and lay down to breath—and meditate. The rope is tied to iron pins which are let into the rock. Occasionally I found where these pins had pulled out. I found three of them in one of the crevices, and one other dangling to the rope. This discovery did not tend to quiet my nerves. The rope is made by knotting together seven smaller ropes, either one of which they say, would hang a man with perfect comfort and safety, but some way this did not occur to me forcibly at the time. After a pause of a few moments I went on, but this time I dragged myself up hand over hand instead of walking and supporting myself by the rope, so that I was soon exhausted. I must confess that my sensations were not exclusively those of weariness or exhaustion; there was an element of anxiety for my personal safety, which must not be overlooked. However, whether from fright or lack of muscle, I was obliged after several more efforts, to slide down the rope and await the return of my more successful companion. He was naturally much elated, and deserves all the credit that attaches to the perilous feat. He is, I believe, the only deaf mute that has ever stood on South Dome...

The reference to the 'deaf teacher named Tilden' was enough to reliably identify the successful climber as Douglas Tilden. He graduated from the California School for the Deaf in Berkeley in June 1879 and was subsequently hired as a teacher at the same school. Douglas was born in Chico, Butte County, California. He lost his hearing and speech after a severe bout of typhoid (or scarlet?) fever at the age of four or five. I checked several Butte county newspapers to see if there is any other information about Tilden's growing up years. Although there was not much about his early days, it was a pleasant surprise to discover that Douglas himself provided a description of that same South Dome climb in a December 1881 letter to a Chico paper. The editor felt compelled to add this preface to the letter: "The following description of a trip to the Yosemite Valley is by Douglas Tilden, ... who will be remembered by residents of Chico of ten or twelve years since, as a bright and intelligent lad of seven or eight years. A severe attack of typhoid fever had left him mute. He was educated at the Institute for the deaf, dumb and blind, and is now teaching in the State Institute. We feel certain that our many readers will peruse the production with true pleasure, at the progress made by the young man, and a just pride in the State Institution for the care of the unfortunate."

Here is the relevant part of Tilden's account:

Weekly Butte Record, Chico, California, December 10, 1881, p. 2

The Yosemite Valley

[The first part of Tilden's article describes a trip with unnamed companions from Berkeley to Yosemite. They began the trip on June 11, 1881, and reached the Valley on June 18, 1881. This part of the text is complementary to W.A.C.'s description in the Indianapolis News. The next section of the article describes waterfalls, peaks and other features that they could see from the Valley floor and from nearby trails. Tilden clearly had a considerable talent for writing, and uses rich vocabulary (although perhaps somewhat archaic by today's standards), to express his fascination with the beauty of the area. The article concludes with his recollection of the South Dome ascent]:

...The next day [Tuesday, June 21, 1881] I ascended the South Dome. A ride of four miles from the bottom of the valley takes you to the base of the rock, from which you have to climb 600 feet by rope to attain the top. This climb was a great experience on my part, both of seeing nature in its grandest phase and of knowing what it was to be in jeopardy of life; and I recur to this subject with a foreboding fear that I shall never look on like scenery again and with the wish that I have seen the last of the unlovely part of the experience. Verily there are not many who would think it no great matter to be suspended in midair by a slender rope, alone and without help, when the muscle was failing, the breathing oppressive and the brain reeling; there are, indeed, few who would think it a child’s fear to give yourself up to the cheerless impression that the rope might be breaking any moment, and upon the strength of this, to measure, with the gleefulness of a maniac, the distance you would be falling. Be that as it may, a greater pleasure cannot be so dearly bought than the one I had that day of viewing a scenery that rivals the Alps. Some natural convulsion had torn the Dome in twain. Looking down from the top—where a single, dwarfed, twisted and snarled oak lives as a Brahma did, eating rice, seed by seed, living yet starving—an awful glimpse of the valley may be had fully one mile below; but how serenely it did smile, cradled between mighty walls! The Mirror lake glowed like the half opened blue eye of a sleeping babe, and from it ran the Tenaya creek, glittering like hushed tears undried when the child fell asleep. To the westward may be seen a perfect wilderness of mountain tops, putting out in jagged and picturesque attitudes; to the left you may see a nameless fall—a precipice flanks it and shoots up into the lordly Cloud's Rest, and beyond it—I saw a picture I shall never forget. Ridge rose upon ridge, dipping their snow-mar[b]led peaks into the sunlight and nursing glaciers at the bottom of the ravine, and meeting the sky in clear outlines. There was snow, snow, snow everywhere. The picture was white and lonely.

D. Tilden

Some years later, Tilden would become widely known as an American deaf and mute sculptor. He first picked up sculpting in 1883. He left Berkeley to attend the Academy of Design in New York in 1887, and then embarked for Paris to study art in May 1888. His first exhibited sculpture won him a medal at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1889. Over the next 25 years, he created a series of sculptures that were installed in many public places in San Francisco and elsewhere. His life and work are well presented on the Internet, e.g., in WikipediA. Two biographical books dedicated to Tilden are also available. However, I haven't found a single reference to his Yosemite adventure in any of the sources that were available to me.

I couldn't close this story of Tilden's ascent without first learning who were his two companions, 'W.A.C.' and 'Truthful James', and how were they connected to him. Tilden didn't give us any direct clues in his article, but a search of the 'Douglas Tilden Papers' collection at the Bancroft Library (UC Berkeley), revealed his correspondence with two people whose initials were W.A.C.: William A. Caldwell, and William A. Coffin. The latter was an American painer, but he was studying in Paris during 1881, and couldn't have been in Yosemite in June of that year. The other person, William Andrew Caldwell (1853-1933) completely fit the bill! He was born and educated in Indiana and became involved in education of deaf people while working as a teacher in the Institution for the Deaf in Indianapolis. That would explain why he later chose the Indianapolis News to describe his Yosemite trip. In 1879 he transferred to the California School for the Deaf in Berkeley, where he met Tilden, who by that time was already a teacher at the School. Caldwell left California soon after the Yosemite trip. He served as a Principal in a school for deaf in Florida. He also worked for a while in Philadelphia, and finally returned to Berkeley in 1892, where he was named Principal's Assistant and then Principal, of the California School for the Deaf. He retired in 1928. And who was Caldwell's 'Truthful James'?

Douglas Tilden in the late 1890s

.

It took some luck to find that. Caldwell reported that they had stayed in a Stockton hotel on the first day of their trip. Fortunately, daily lists of hotel guests in Stockton for mid-June were available in the Stockton Independent newspaper. Indeed, there were entries for D. Tilden and W. A. Caldwell, both "from Berkeley". But there was another guest from Berkeley the same night in the same hotel: W. E. Zander! It was then easy to confirm that William Edward Zander (1859-1923) was the third member of the Tilden-Caldwell Yosemite party. Zander worked as a clerk at the California School for the Deaf in Berkeley from about 1880 to 1886. His mother, born Sarah Matilda Griswold was a close relative to Bret Harte's wife, Anna Harte nee Griswold. This would explain Caldwell's choice of Harte's literary character 'Truthful James' in nicknaming Zander. The final domino fell in place when I found Geo. Fiske's photo of our three travelers and their 'amazing' donkey (the donkey was mentioned in the Indianapolis News article, see above). The photograph, posted at the Oakland Museum of California website, is murky and badly mislabeled, but in a way, it still nicely ties everything together.

Douglas Tilden (1860-1935) was 21 at the time of his Half Dome ascent. From his thirties to his mid fifties he enjoyed wide popularity and fame among art lovers.

However, in the aftermath of WWI his style of sculpting was superseded by new trends, and Tilden’s star went quickly into decline. With no new commissions, in the early 1920s he had to accept a job of a machinist in a San Francisco factory. He then moved to Hollywood and began to sculpt various extinct animals for movies. This must have been a humiliated experience, but at least it enabled him to have a steady income. When even that work dried up, he returned to Berkeley. Strugling constantly against powerty, impoverished and probably embittered, he died there alone on August 4th, 1935. A neighbor found him dead on the kitchen floor two days later. He was 75. Find more about Tilden's life and struggles in his 1935 obituary. Sadly, his art work is disappearing from public places. The trend actually began back in 1906, when one of his first major sculptures, The Tired Boxer (1890), melted in the fire following the San Francisco earthquake. The latest example is from 2020, when Tilden's statue of Junipero Serra (1906) was toppled and splashed with red paint by vandals, and then permanently removed from San Francisco's Golden Gate Park. Ironically, a sentence in the 1935 obituary reads: "His statue of Junipero Serra in Golden Gate Park... will stand forever as silent testimony to his great art."

Ascenders: Anderson, Frank Gassaway, Henry Osborne, (July 21, 1882)

Frank Gassaway, whose nom de plume was Derrick Dodd, was writing popular travel reports for the San Francisco Evening Post. I don't have access to that newspaper. Fortunately, a description of his 1882 trip to Yosemite got reprinted in the book Summer saunterings, which is available online. The book has several paragraphs on Gassaway's and Henry Osborne's Half Dome ascent in mid-July of 1882. Here is what Gassaway said:

Summer saunterings, by Derrick Dodd, San Francisco, 1882:

[p. 122] ...As a standpoint for the landscape viewer, the polished summit of

[Half Dome] is incomparably the finest in the whole range, towering as it does

five thousand feet above the Valley floor and commanding its entire scope,

from east to west. The drawback to its general enjoyment by the tourist is the

undeniably hazardous nature of the present means of ascent, which from

the top of the horse-trail to the apex of the eminence is by means of a rope

nine hundred feet long. This cord lies upon the slippery surface of the granite slope,

the angle never being less than forty degrees. The marvel of the matter is

how this cord was first placed on that air-line trail by the spider-footed

Geo. Anderson, a guide of the greatest strength and most iron nerve.

A man ascending this dizzy slant presents about the relative appearance of

a fly walking up the side of an inverted goblet. Very few visitors care

to attempt it, unless under the supervision of this guide, Anderson, whose

wonderful coolness was acquired as a sailor. The cord itself is hardly

calculated to inspire the fullest confidence, being composed of

seven thicknesses of common, hay-bale-rope. This, however, is knotted every

few inches to assist the hands, besides which the climber can rest at certain

intervals and anoint the soles of his feet with fresh mucilage, a bottle of

which he carries in his vest pocket for the purpose...

We also have a description of the same trip by the other climber, Henry Z. Osborne. His recollection of this ascent was published in a letter to the Editor of the

Los Angeles Times, thirty-tree years after the actual event. He was reacting to an earlier article about

the photographer Arthur Pillsbury in the same paper. Note that Osborne placed the climb in 1881, but it really happened in 1882:

Los Angeles Times, August 17, 1915, p. II5

Climbing the Half Dome

Los Angeles, Aug. 16 — To the Editor of the Times: The feat of

seventeen college students, several from this city, accompanied by

the photographer A. C. Pillsbury, of climbing the Half Dome in

the Yosemite Valley [in August 1915]...,

is a very notable achievement in mountain climbing.

But it is not quite accurate to say that "this is the first time on record

that the top of the Dome has been reached by human beings", although it is

probably true it has not been done during the last thirty years.

In the year 1881, when I had less sense and less avoirdupois

than now, accompanied by Frank Gassoway [actually: Gassaway],

a San Francisco newspaper man,

who wrote under the nom de plume "Der[r]ick Dodd", I made the ascent of the

Half Dome.

I came into the valley horseback from Mono Lake, crossing by the way of

Mill Creek Canyon, Mt. Dana, Tioga, the Tuolumne meadows and Lake Tenaya,

and meeting Mr. Gassoway in the valley, we agreed together to climb the

Half Dome, or the South Dome, as it is sometimes called.

We rode horseback from the valley to the Saddle, which is 960 feet below

the summit of the Dome, and from that point we climbed the rock by aid of

a rope about a half inch in diameter, which had been placed there by a sailor

named Anderson in the early seventies. He had set iron staples with rings

in the rock about seventy-five feet apart, and the rope was attached

to each of those staples. Many venturesome people climbed the Dome while

this rope was in place. At that time the rope was quite weather-worn

and many of the staples had become loose and detached from the rock.

These rattling on the surface of the granite were very disconcerting

during the climb...

From a distance the Half Dome

looks perfectly smooth and shines like glass in the sun, but in reality

it is of granite of rather coarse texture, and the grain of the rock,

with occasional cracks, give a slight foothold.

This rope, which was regarded as dangerous, was taken down that year,

and no one has ever ascended the Half Dome in the thirty-odd years since,

until the feat of Pillsbury and the students, which was really a very

remarkable one.

On the top of the rock, 9500 feet above the sea level, there is an

acre or so comparatively level, and on this were many bones of sheep,

which had climbed the steep dome, but could not raise sufficient courage

to descend, and died at the top rather than make the attempt.

H. Z. Osborne

Henry Zenas Osborne (1848-1923), was 33 when he made this Half Dome ascent.

He was born in New Lebanon, New York, and came to Bodie, California in 1878,

where he edited and managed the Daily Standard and

founded the Bodie Daily Free Press. He made the trip to Yosemite

during his Bodie years. In 1884, he moved to Los Angeles, and acquired the

Evening Republican and the Evening Express, which he

directed until 1897. A biographical note from 1889 states that

"Mr. Osborne has a family of wife and five children, — four sons and one

daughter, — and a pleasant home in Los Angeles". After 1897,

Osborne pursued a political career, which culminated

in his election as a Republican representative to the Congress in 1916, the post he held

until his death in 1923.

Frank Harrison Gassaway (1848-1923), was only nine months older than Osborne,

and had the same life span as his Yosemite partner. They both died early

in 1923. Frank, an accomplished

poet and reporter working in San Francisco, was 34 when he climbed the Dome.

He was born in Maryland or Washington, D.C., and came to

California in or before 1876. By that time, two of

his most popular patriotic poems were already published:

The Pride of Battery B (4th U.S. Light Artillery),